|

Throughout history, the social roles played by images have changed dramatically. For example, art's origins as an expression of religious tenets evolved over time to its role as an object of value restricted to the wealthy classes, and eventually to the context of art commodification today, in which consumers can purchase art in the form of reproductions. Similarly, the photograph has played many different social roles since it was developed in the early nineteenth century, including those of art, science, marketing, the law, and personal memory. The emergence of electronic imaging in the late twentieth century, with digital imaging, the Internet, and the World Wide Web, has radically altered the distribution and social meaning of images. Hence, both the conventions of imaging and the concepts of the visual have changed through- out history.

We look at images of the past differently today than they were viewed during the time in which they were created. A viewer may make assumptions about the historical status of an image from its style, medium, and formal qualities. For instance, we might assume that a painting composed in a classical style was made prior to the modernist art period of the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, or that a brown sepia-toned, black-and-white photograph, or a faded color image, is a historical image.

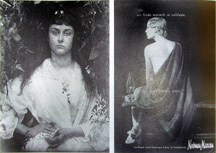

There are many aspects of the photograph on the next page, for instance, that indicate its historical status. As viewers, we can make certain assumptions about when it was made, even if we know nothing about its origins. Its original tone is a soft brown sepia color, which was a convention of nineteenth-century photography and hence signifies an aged image. The woman in the portrait is dressed in a style of a different era, and the soft focus on the edges of the frame give a faded sense of time. She is framed by branches of a tree, and stares boldly at the camera. This image is, in fact, photographer Julia Margaret Cameron's 1872 portrait of Alice Liddell, the inspiration for Alice in Wonderland. It is possible for this image to have been made today, using older imaging techniques and nineteenth-century clothing styles. Yet, its meaning would then be different. It would then signify, among other things, a reference to a historical style rather than a simple portrait.

Advertisers have often used the codes of classical style to attach to their products both a sense of history and a nos talgia for previous times. This is intended to add concepts of value and class to that product, so that it will evoke both tradition and taste. In the ad above, for instance, the classical pose of the model evokes the history of painting of female nudes, and thus attaches to the product—a designer shawl—the qualities of art and upper-class taste. The old lantern, wooden bench, and 1920s hairstyle are signifiers of the past and tradition. The phrase, "art becomes you," thus suggests to consumers r that they can themselves acquire the attributes of classical art through the purchase of the shawl. As we shall discuss in Chapters 6 and 7, the signification of history in visual images now exists in a broad array of remakes, parodies, and images of nostalgia. talgia for previous times. This is intended to add concepts of value and class to that product, so that it will evoke both tradition and taste. In the ad above, for instance, the classical pose of the model evokes the history of painting of female nudes, and thus attaches to the product—a designer shawl—the qualities of art and upper-class taste. The old lantern, wooden bench, and 1920s hairstyle are signifiers of the past and tradition. The phrase, "art becomes you," thus suggests to consumers r that they can themselves acquire the attributes of classical art through the purchase of the shawl. As we shall discuss in Chapters 6 and 7, the signification of history in visual images now exists in a broad array of remakes, parodies, and images of nostalgia.

Realism and the history of perspective

One way to understand how the meaning of images has changed throughout history is to examine the role of realism in art. Changes in the aesthetic style of images do more than simply chart the history of art and visual culture, they can also indicate the development of different kinds of world views. By examining the stylistic changes of the history of Euro-American visual culture, we can see how images indicate changing ways of seeing the world.

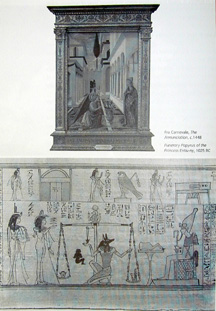

Realism has been a fundamental goal of many styles of art, because art has often functioned to reflect society and nature back to its spectators. While the history of religious art has been concerned with depicting not the real world but the metaphysical world of myth and religious figures and events, painting has had a very long tradition of representing the human figure and the world in which we live. The desire to have images represent either the real world or an imagined world has changed dramatically throughout different moments of history. Similarly, the concept of what makes an image realistic has changed throughout history and varies between cultures.

One of the fundamental shifts of the depiction of reality in the history of Western art took place with the development of perspective as a convention of European art. The invention of perspective in the mid-fifteenth century was the result of a Renaissance interest in the fusion of art and science. It is a mechanically inspired technique to make paintings appear more realistic in their translation of three-dimensional space to a two-dimensional image. To use linear perspective to create an image, the painter has to designate at least one vanishing point and design the objects within the image to recede in size toward that point. Techniques of perspective demand that the objects and people depicted in the background of images be painted smaller and along receding planes. In the 1448 depiction of the annunciation on the next page, a motif in Christian art by Fra Carnevale, the buildings and landscape are scaled to be increasingly small as they recede toward a central vanishing point This has the effect of drawing the viewer's eye toward this central point, and in giving the image a depth which, in this case, foregrounds the figures. One of the fundamental shifts of the depiction of reality in the history of Western art took place with the development of perspective as a convention of European art. The invention of perspective in the mid-fifteenth century was the result of a Renaissance interest in the fusion of art and science. It is a mechanically inspired technique to make paintings appear more realistic in their translation of three-dimensional space to a two-dimensional image. To use linear perspective to create an image, the painter has to designate at least one vanishing point and design the objects within the image to recede in size toward that point. Techniques of perspective demand that the objects and people depicted in the background of images be painted smaller and along receding planes. In the 1448 depiction of the annunciation on the next page, a motif in Christian art by Fra Carnevale, the buildings and landscape are scaled to be increasingly small as they recede toward a central vanishing point This has the effect of drawing the viewer's eye toward this central point, and in giving the image a depth which, in this case, foregrounds the figures.

The technique of perspective appears to us to be realistic precisely because it is a stylistic convention that dominates in Western images to this day. Prior image conventions, for instance, used flat space with little sense of depth, and some ancient styles, such as ancient Egyptian art, depicted the size of an object or person according to its social importance rather than its distance from the viewer. In this Egyptian drawing on papyrus, the figures are flattened in space and there is little sense of depth. The figures exist within an abstract space, and tell a narrative in relation to each other and the written text. Yet, this work would have been understood in ancient Egypt to represent the real world.

Perspective redefined painting styles from the fifteenth century on. !t is not simply a visual technique but a way of seeing, one that indicates a change in the world view of Renaissance Europe at the time that it became an aesthetic convention. The Renaissance, which began in Italy in the early fourteenth century and reached its height throughout Europe in the early sixteenth century, has been defined as a time of intellectual and artistic resurgence that was fueled by a renewed interest in Classical art and literature. The Renaissance represented a conscious embrace of culture, science, art, and politics. One of the primary aspects of Renaissance perspective is its designation of a single spectator in space. Perspective emphasizes a scientific and mechanical view toward ordering and depicting nature, and focuses a work of art toward a perceived viewer. The spectator defines the center of the image. Whereas, for instance, Medieval imaging conventions assumed that there could be many vantage points from which a scene could be depicted, perspective demanded that one, unique point be established. Thus, it has been said that the technique of perspective turns the viewer into a "god," whose view is the defining position from which to look at a scene. As art critic John Berger has written, "Every drawing or painting that used perspective proposed to the spectator that he was the unique center of the world "4

In addition, perspective took hold in Europe in the same era as the emergence of new ideas in astronomy, such as Copernicus's concept of the earth rotating around the sun rather than being the center of the universe, ideas which radically challenged the Church's view of a god-centered universe. As perspective gained prominence in fifteenth-century painting, it formed part of a larger set of social changes, including the embrace of science in the emerging Scientific Revolution. One of its primary early proponents was Leonardo da Vinci, whose work is famous in the history of art for its integration of principles of science and art. The emphasis on a single spectator in perspective thus can be seen in the context of changing notions about religious definitions of the world and the beginning of a shift in social values from religion to science. Whereas previous cultures, such as Classical Greece, had philosophical debates about realism in art, and rejected the use of techniques such as perspective as a form of trickery, the Renaissance era embraced the idea that it was art's social function to represent the real as closely as possible. Indeed, da Vinci wrote in his diaries, `'ln art we may be said to be grandsons to God.... Have we not seen pictures which bear so close a resemblance to the actual thing that they have deceived both men and beasts?"

The artists who first began working with the technique of perspective in the fifteenth century were enthusiastic about its results. Here, they felt, was a scientific approach that helped them to create objective images of reality. Hence, perspective reveals the desire for art to be an objective, as opposed to subjective, depiction of reality. Yet, though it may seem to be a realistic depiction of the world, perspective is a highly reductive, abstract form of representation. It is a convention that makes images that use perspective seem like reality. Among other things, perspective reduces the relationship between eye and object to a single exchange in space. The spectator is situated in perspective as having a view from one specific place. It has been argued by many art historians and others that human vision is infinitely more complex than this notion of a stationary viewer. When we look, our eyes are in constant motion, and any sight we have is the composite of many different views and glances. In addition, much contemporary philosophy has emphasized that the view of the spectator affects the thing looked upon. As we noted in Chapters 2 and 3, a central part of looking is about the particular relationship of a spectator to a specific image at a specific moment in time and place. The world of perspective indicates the desire for vision to be stable and unchanging and for the meaning of images to be fixed, when the act of looking is in fact highly changeable and contextual.

The technique of perspective also shifted the role of space in images, allowing space to dominate over the figures in the frame. As we can see in the painting of The Annunciation, the architectural forms and space dominate in the image, almost at the expense of the human figures in the foreground. Space is organized in perspective as linear and uniform rather than symbolic. This scientifically defined sense of space related to a broader set of philosophical developments. French philosopher Rene Descartes, who lived in the seventeenth century, is responsible for many contemporary concepts of space which can be related to his privileging of the visual. Descartes's concept of space, known as Cartesian space, is defined as that which can be mathematically mapped and measured. A Cartesian grid refers to the organization of space through three axes, each intersecting the others at 90 degrees to produce three-dimensional space. Cartesian space is derived from Descartes's theories about rational ways of viewing the world and is contingent on the idea of an all-knowing, all-seeing human subject. Descartes was very influential in the legitimation of ideas about visual observation forming the basis for evidence, which is one of the foundations of empiricism. He famously wrote: "A11 the management of our lives depends on the senses, and since that of sight is the most comprehensive and noblest of these, there is no doubt that the inventions which serve to augment its power are among the most useful that there can be."3 Thus through the development of perspective and the subsequent philosophical turn toward the visual, the relationship of science/technology and vision is firmly established in Western philosophy. In Chapter 8, we will discuss in more detail the implications of the relationship between the visual and scientific or legal evidence.

Realism and visual technologies

As we can see with the fusion of science and art in the technique of perspective, changing historical understandings of images have been directly influenced by imaging technologies. The privileging of both science and the visual in Western philosophy emerged after the Scientific Revolution that took place from the mid-fifteenth through the seventeenth century. During this time period, developments in science, in fields such as navigation, astronomy, and biology, prompted radical changes in the world view, changes that eroded the dominant role of the Church. Many new scientific ideas, such as Galileo's theories about planetary movement, were seen as a threat to the Church, and were the source of difficult struggle (Galileo was tried, for instance, for heresy for his scientific ideas). However, by the eighteenth century, science had emerged as a dominant social force. In the Enlightenment, an eighteenth-century intellectual movement, there was an embrace of the importance of science, and the concepts of rationalism and progress. The Enlightenment promised that the power of human reason would overcome superstition, end ignorance through the development of scientific knowledge, bring prosperity through the technical mastery of nature, and introduce Justice and order to human affairs. The rationalism and elevation of science and technology that we saw with Descartes was thus firmly established in this time period, and would lay the foundations for modernity.

The history of visual images can be seen in light of the development of science and technology. It is a history of visual technologies as well, from the invention of perspective to photography, film, television, and, more recently, digital imaging. Seen through this framework of image technology, the history of image production in Western culture can be viewed in four general periods: (1) ancient art produced prior to the development of perspective in 1425; (2) the age of perspective until the era of the mechanical, including the Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Romantic periods (roughly the mid-fifteenth century until the eighteenth-century), a time period that includes the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment; (3) the modern era of technical developments with the rise of mechanization and the Industrial Revolution, including the development of photography in the 1830s, that made image reproduction and mass media possible (the mid-eighteenth century until the late twentieth century); (4) and the postmodern era of electronic technology, computer and digital imaging, and virtual space (overlapping with the mechanical, approximately from the 1960s until the present). The rest of this chapter will concentrate on these last two time periods and the social and cultural views they represent.

Technologies of imaging, such as perspective or photography, are not simply sitting out there in the world, waiting to be invented. To say that a given technology dictates its invention is to engage in technological determinism. Technological determinism is the belief that technology determines social effect and change, and that it is autonomous and hence separate from social effects. In this book, we argue against technological determinism. Instead, we look at technologies (specifically visual technologies) as the products of particular social and historical contexts. They emerge from collective cultural and social desires. In other words, it can be argued that technologies have important and influential effects on society, but they are also themselves the product of their societies and times, and the ideologies that exist within them.

For instance, the scientific elements of the technique of perspective existed prior to its "invention." As we mentioned before, the Greeks understood the basics of perspective, yet they rejected it as a technique because it was in contrast to certain fundamental philosophical ideas that were prevalent in Greek culture—that one should not paint a painting that might "trick" a viewer into thinking it was real, for instance. The development of perspective as a technique was the outcome of the social views of European culture in the early fifteenth century, including an emergent interest in scientific process. Similarly, many of the chemical and mechanical elements necessary to produce photographic images existed prior to when photography was invented simultaneously by several people working in different countries in the 1 830s. Indeed, some art historians have argued that photography could not have emerged as a visual technology until Western artists had begun to paint in the language of photography—not rigidly composed realist works but paintings that were like snapshots, seemingly life-like and spontaneous. In addition, the early uses of photography, which was instantly popular, were both institutional (for medical, legal, and scientific uses) and personal (an early widespread use of photography was for portraits). These uses influenced the ways that photographic technology developed.

It could thus be said that photography emerged as a visual technology because it fit certain emerging social concepts and needs of the time— modern ideas about the individual in the context of growing urban centers, modern concepts of technological progress and mechanization, and the rise of bureaucratic institutions in the modern state. In combining scientific technique with art, like the technique of perspective, yet also deploying a mechanical device, photography is in many ways the visual technology that helped to usher in the age of modernity. It could thus be said, in the terms of Michel Foucault that we discussed in Chapter 3, that photography emerged as a medium when certain discourses of science, law, technology, and modernity made its social roles possible.

The historical moment when photography was developed and became popular, from the early nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century, when the question of reproduction became crucial to the meaning of images, is considered to be the height of modernity. Modernity is a term that refers both to a specific period of time (dating approximately from the sixteenth century until the mid-twentieth century, with its height in the nineteenth century) and to a particular era of social development in Euro-American culture and modernism to a style of Western art (dating approximately from the turn of the century to the late twentieth century). The modern era is characterized by a sense of both upheaval and possibility that accompanied the increased urbanization of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as large numbers of people moved from agrarian, rural lifestyles into growing cities. It is defined by industrialization and mechanization, the rise of the modern

political state, and the increased bureaucratization of daily life. These social factors contributed to a breakdown of traditions and a sense of collective alienation, yet also to an ernbrace of the future with both anxiety and utopian optimism. (We will discuss modernism and postmodernism at more length in Chapter 7.)

Photography is in many ways the mechanical realization of perspective, and its effect on painting was profound. With the development of a camera device that could produce realistic images of the world, the social role of painting changed dramatically. Whereas painting had functioned throughout most of Western history as a means to produce an idealized view of the world, specifically through the world view of the Church, it had become increasingly a tool of realism after the invention of perspective The invention of photography was greeted by such proclamations of its verisimilitude, that some even suggested it had redefined human vision altogether. French writer Emile Zola even wrote at the time, "We cannot claim to have really seen anything before having photographed it."4 Many thus felt that the camera could do a "better" job of producing realistic images of the world than a painting, and this allowed painters to think of painting in new ways not always tied to realism or to the ideology of fixed perspective.

As a consequence, many styles of modern art that followed the invention of photography defied the tradition of perspective. Impressionism, for instance, was an art movement of the late nineteenth century that featured works that used visible brushstrokes and impressionistic depictions of light to capture a sense of human vision. The style of Impressionism shifted its focus to light and color and aimed for a visual spontaneity. The impressionist work is not a moment captured in time, like a photograph, but an image that evokes the ongoing play of light and color in the experience of looking. Impressionism was greeted, as many changes in representational style are, as a disturbing way of looking (prompting French cartoonists to predict that the images would cause women to miscarry). It remains an extremely popu~ar style of art today.

One of the primary figures of Impressionism was Claude Monet, whose works have a particular emphasis on the play of light and water. Monet examined the process of looking by painting many different works of the same scene. He made some -twenty paintings, for instance of the cathedral in Rouen, each a portrait of different light and color. In works such as these, Monet demonstrated the complexity of vision and also established it as a fluid process. The Rouen Cathedral never looks the same; it is not simply one set view, but many impressions. The act of seeing is thus established in these works as active, changing, never fixed, a process of thought. In later years, .Monet would paint many versions of his now famous garden in Giverny. One of the primary figures of Impressionism was Claude Monet, whose works have a particular emphasis on the play of light and water. Monet examined the process of looking by painting many different works of the same scene. He made some -twenty paintings, for instance of the cathedral in Rouen, each a portrait of different light and color. In works such as these, Monet demonstrated the complexity of vision and also established it as a fluid process. The Rouen Cathedral never looks the same; it is not simply one set view, but many impressions. The act of seeing is thus established in these works as active, changing, never fixed, a process of thought. In later years, .Monet would paint many versions of his now famous garden in Giverny.

New ways of looking were a primary focus of the French avant-garde in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. What it means to look was thus a central concern of modern art at a time of rapid social change that included the increased social role of photography and a sense of upheaval. One of the central movements of the avant-garde at the turn of the century was Cubism, a style that was associated initially with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. The painters who worked in Cubism were interested in depicting objects from several different points of view simultaneously. Cubism was thus a style resistant to the dominant model of perspective; it proclaimed that the human eye is never at rest upon a single point but is always in motion. The Cubists painted -. objects as if they were being viewed from several different angles simultaneously, and focused on the visual relationship between objects. In the painting by Georges Braque on the next page, a rendering of realistic space and light has been discarded for a kinetic view of a guitar player through different angles and fragments. The painting is intended to show a view of a man with a guitar composed as a series of simultaneous glances. This was, according to the Cubists, a means of depicting the restless and complicated process of human vision. We could compare this image to another still life, the seventeenth century Dutch still life by Pieter Claesz, which we discussed in Chapter 1. Both images are still lifes, but B raque's vision defies the singular perspective of Claesz's realist image. Although each painting presents itself as a representation of how we really see, the Claesz painting posits a singular spectator looking toward the image and the Braque offers the restless view of a spectator in constant motion. It is important to note that the Cubists were interested in depicting reality, in creating a new way of looking at the real. John Berger has written, "Cubism changed the nature of the relationship between the painted image and reality, and by so doing it expressed a new relationship between man and reality."5 raque's vision defies the singular perspective of Claesz's realist image. Although each painting presents itself as a representation of how we really see, the Claesz painting posits a singular spectator looking toward the image and the Braque offers the restless view of a spectator in constant motion. It is important to note that the Cubists were interested in depicting reality, in creating a new way of looking at the real. John Berger has written, "Cubism changed the nature of the relationship between the painted image and reality, and by so doing it expressed a new relationship between man and reality."5

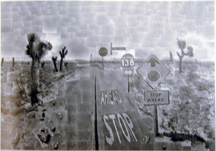

Modernist styles such as Impressionism, Cubism, and, later, Abstract Expressionism were all, among other things, responses to the dominance of perspective in Western art for centuries; each declared vision to be infinitely more subjective and complex. What realism is in images has thus changed dramatically throughout history, and continues to change. The idea that a perspective based realistic view is actually no more than one of the many ways of representing human vision has been taken further by many contemporary artists. For instance, in this photo collage, David  Hockney composes an image of a desert intersection through many snapshots taken from different positions. Where is the "real" image here? At what "moment" was this image taken? Where is the spectator of this image positioned? Hockney’s work suggests that this mundane roadside is never one view but many views from many perspectives over time. His image is a portrait of the vibrancy of everyday vision. Hockney composes an image of a desert intersection through many snapshots taken from different positions. Where is the "real" image here? At what "moment" was this image taken? Where is the spectator of this image positioned? Hockney’s work suggests that this mundane roadside is never one view but many views from many perspectives over time. His image is a portrait of the vibrancy of everyday vision.

The reproduction of images

One of the primary aspects of the relationship of technology to the history of imaging is that of image reproduction. In the context of modernism, with the rise of photography in the early nineteenth century and the invention of film in the 1 890s, image conventions changed in significant ways. Hence, of the four eras we defined earlier through which the relationship of technology ancd images can be charted, the third era of modernism is defined in many ways by the new capacities of image reproduction and the development of the mass media. Photographic, cinematic, and television images are infinitely reproducible, and that fact has radically changed the role of images in society. In Chapter 5, we will discuss the rise of mass media. In this chapter, we will focus on the effect of image reproduction on the social role of images in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Prior to the development of technologies that could reproduce images, a work of art was considered to be unique and original, its meaning tied to the place where it resided (which was often a church or palace). These works of art were always potentially reproducible, indeed the practice of creating replicas of famous works of art has always been quite common. However, the mechanical reproduction of art is quite different from the more inexact creation of replicas. Mechanical reproduction changes the meaning and value of an image and, ultimately, the role images play in society. Walter Benjamin, a German critic of the early twentieth century, wrote a famous essay in 1936 about this cultural shift, entitled "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Benjamin was an early member of the Frankfurt School, which we will discuss in Chapter 5. His essay, like many of his writings, is still highly influential today, precisely because it explains and predicts the changing visual culture of the twentieth century. Prior to the development of technologies that could reproduce images, a work of art was considered to be unique and original, its meaning tied to the place where it resided (which was often a church or palace). These works of art were always potentially reproducible, indeed the practice of creating replicas of famous works of art has always been quite common. However, the mechanical reproduction of art is quite different from the more inexact creation of replicas. Mechanical reproduction changes the meaning and value of an image and, ultimately, the role images play in society. Walter Benjamin, a German critic of the early twentieth century, wrote a famous essay in 1936 about this cultural shift, entitled "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Benjamin was an early member of the Frankfurt School, which we will discuss in Chapter 5. His essay, like many of his writings, is still highly influential today, precisely because it explains and predicts the changing visual culture of the twentieth century.

There are many technologies of imaging that can produce multiple similar images. Printmaking techniques such as engraving, etching, and woodcuts were developed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and lithography in the early nineteenth century. It has been argued, most notably by art historian William Ivins, that while great emphasis has always been placed on the social impact of the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century by Johann Gutenberg, the slightly earlier discovery of how to print pictures and diagrams was tremendously important to the emergence of modern life and thought. Without prints, Ivins states, "we should have very few of our modern sciences, technologies, archaeologies, or ethnologies—for all of these are dependent, first or last, upon information conveyed by exactly repeatable visual or pictorial statements."6

The importance of the "exactly repeatable visual or pictorial statement" was central to the dissemination of knowledge. However, the medium of photography changed the status of the image further by making it possible to reproduce pre-existing works of art, such as paintings and frescoes, which were previously unique. Benjamin wrote that this technological change had a profound influence on the meaning of art in society. For instance, the invention of photography coincided with a cult of originality. Artists would often in the past produce several versions of the same painting, and there were traditions of making replicas of works, usually by the artist or under his/her supervision, in the same medium. However, with the rise of reproduction, these practices disappeared. Instead, a reaffirmation of the unique image, one that had more value, took place precisely at the time when that original image could be reproduced into copies by the mechanical photographic camera.

Benjamin argued that the one-of-a-kind art work has a particular aura to it. Its value is derived from its uniqueness and its role in ritual, meaning that it may carry a kind of sacred value, whether religious or not. Indeed, it is because of the fact that it is one of a kind that it retains a sacred status. He wrote, "Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be."7 It is precisely this "presence in time and space" that Benjamin refers to as the aura of the image, a quality that makes it seem authentic.

The concept of authenticity is crucial to the way in which images are perceived to have value. Benjamin points out that the original of a reproduction is understood to be more authentic than the copies made from it. In other words, in Benjamin's terms, authenticity cannot be reproduced. Traditionally, authenticity has meant "genuine, reliable, not false or copied," indeed, the idea that something is more `'real." Yet, the concept of authenticity is used in many different ways today. For instance, an advertisement might claim that its product is "authentic" in order to sell it. In the ad on the next page, authenticity is defined as "something new that's been there all along," in an attempt to sell both tradition and newness simultaneously. The idea of authenticity is something that advertisers often attempt to attach to consumer products through codes of realism. Jerky "amateur" camera work and "natural" sound and lighting are used to create a realist effect, selling the idea that nothing in the ad has been orchestrated or faked, and references to tradition are used to sell identities that cannot be acquired simply by purchasing a product. For instance, Ralph Lauren's western wear acquires the code of authenticity by appearing to be just like the clothes of cowboys on the ranch; Reebok and Nike use images of inner-city basketball courts (presumably the most "authentic" place where basketball is played) to attach the quality of authenticity to high priced sneakers. It could be argued that authenticity is about being genuine and original. Paradoxically, we live in a world in which the concept of authenticity is routinely reproduced, packaged, sold, and bought.

We live in a society that is also permeated with mass-produced images. The idea that only a one-of-a-kind image can be authentic holds little currency in our world. Many copies can exist of a photographic image, each of equal value, and cinematic, television, and computer images consist of many simultaneous images all at once. Their value lies not in their uniqueness but in their aesthetic, cultural, and social worth. As we discussed in Chapter 1, a television news image can be considered valuable because it can be seen simultaneouslyon many screens at the same time. However, Benjamin's central point is about the effect of reproduction upon the image, and how the meaning of an original image changes when it is reproduced. Many famous paintings have been reproduced in art books and on posters, postcards, and T-shirts. What effect does this have on the quality of the original? The original is more valuable, in both financial and social terms, than the copies. However, Benjamin wrote that this value has changed, since it comes not from the uniqueness of the image as one of a kind, but rather from it being the original of many copies.

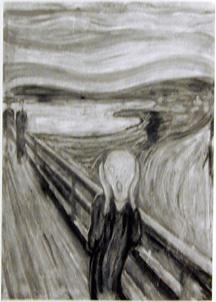

Mechanical reproduction means that famous works of art are more accessible to people, because they can view these images in books and even own copies of them to put on their own walls in the form of posters. One could say that this demystifies these works of art and makes them seem less untouchable and magical than they may appear in the original. One of the most fundamental consequences of reproduction is that an image that before had existed within a single place can now be seen in many different contexts: an art history book, a bulletin board, an advertisement. The painting, The Scream, shown on the next page, was painted by Edvard Munch in 1893. Munch was adept at depicting the angst of modern life, and his painting has become an icon for neurosis and fear. In the original, the red sky creates an ominous feel and the figure, more a homunculus than a man, is a ghostlike embodiment of anxiety. Like other famous paintings, The Scream has been reproduced as a postcard and poster, but because of its iconic value, it has also proliferated as a kind of kitsch object—an inflatable figure, a birthday card, a key chain, a refrigerator magnet. It was also used as a reference in the 1996 film Scream, in which the killer wears a Scream-inspired mask. Importantly, the meaning of the image changes with each context. For instance, when The Scream is an inflatable figure, it is almost impossible to invest the image with the deep seriousness of its original terror. Rather, it is intended to make us ~augh aboutthe stress of everyday life, in effect to laugh at modern angst. Similarly, when The Scream appears on a 40~-h birthday card, it is used for humorous effect. One could say, then, that this image has the op-posite effect from its original when it is reproduced as a kitsch object of questionable taste. Mechanical reproduction means that famous works of art are more accessible to people, because they can view these images in books and even own copies of them to put on their own walls in the form of posters. One could say that this demystifies these works of art and makes them seem less untouchable and magical than they may appear in the original. One of the most fundamental consequences of reproduction is that an image that before had existed within a single place can now be seen in many different contexts: an art history book, a bulletin board, an advertisement. The painting, The Scream, shown on the next page, was painted by Edvard Munch in 1893. Munch was adept at depicting the angst of modern life, and his painting has become an icon for neurosis and fear. In the original, the red sky creates an ominous feel and the figure, more a homunculus than a man, is a ghostlike embodiment of anxiety. Like other famous paintings, The Scream has been reproduced as a postcard and poster, but because of its iconic value, it has also proliferated as a kind of kitsch object—an inflatable figure, a birthday card, a key chain, a refrigerator magnet. It was also used as a reference in the 1996 film Scream, in which the killer wears a Scream-inspired mask. Importantly, the meaning of the image changes with each context. For instance, when The Scream is an inflatable figure, it is almost impossible to invest the image with the deep seriousness of its original terror. Rather, it is intended to make us ~augh aboutthe stress of everyday life, in effect to laugh at modern angst. Similarly, when The Scream appears on a 40~-h birthday card, it is used for humorous effect. One could say, then, that this image has the op-posite effect from its original when it is reproduced as a kitsch object of questionable taste.

The changes in visual culture that have taken place with the emergence of digital imaging have also changed the contexts in which famous works of art have been reproduced. The impact of computers and digital media on Western visual culture has often been compared to the impact of perspective during the Renaissance. Hence, there are many references in digital culture to the Renaissance and in particular to Leonardo da Vinci as an icon of that era's merging of science of art. For instance, one of the computer art field's publications, Leonardo, uses his name to signify the powerful impact of the computer in changing paradigms in art. Leonardo's painting, the Mona Lisa, painted in 1503, has also been used to imply the computer's value as a high art form and not just a commercial technique, precisely because, as we noted in Chapter 1, it is known as one of the most famous paintings in the world. A reproduction of the Mona Lisa was one of the first images to be scanned and digitally reproduced on a computer in 1965, along with a portrait of computer scientist Norbert Wiener (who coined the term "cybernetics"). Copies of this "digital masterpiece" are sold on the World Wide Web, where the image is described as "unique." In this case, unique means not one of a kind, but unusual. One such "unique" copy of the digital Mona Lisa hangs in the Computer Museum in Boston. One might ask the question, who is the "artist" behind this "masterpiece" reproduction, Leonardo da Vinci (who had no say in its digitization), the computer scientist who was in charge of its production process, or the workers at the laboratory that made the reproduction technology possible? The changes in visual culture that have taken place with the emergence of digital imaging have also changed the contexts in which famous works of art have been reproduced. The impact of computers and digital media on Western visual culture has often been compared to the impact of perspective during the Renaissance. Hence, there are many references in digital culture to the Renaissance and in particular to Leonardo da Vinci as an icon of that era's merging of science of art. For instance, one of the computer art field's publications, Leonardo, uses his name to signify the powerful impact of the computer in changing paradigms in art. Leonardo's painting, the Mona Lisa, painted in 1503, has also been used to imply the computer's value as a high art form and not just a commercial technique, precisely because, as we noted in Chapter 1, it is known as one of the most famous paintings in the world. A reproduction of the Mona Lisa was one of the first images to be scanned and digitally reproduced on a computer in 1965, along with a portrait of computer scientist Norbert Wiener (who coined the term "cybernetics"). Copies of this "digital masterpiece" are sold on the World Wide Web, where the image is described as "unique." In this case, unique means not one of a kind, but unusual. One such "unique" copy of the digital Mona Lisa hangs in the Computer Museum in Boston. One might ask the question, who is the "artist" behind this "masterpiece" reproduction, Leonardo da Vinci (who had no say in its digitization), the computer scientist who was in charge of its production process, or the workers at the laboratory that made the reproduction technology possible?

The questions of authorship and artisti-c ownership become even more complex in contexts where consumers are invited to reproduce art masterpieces as their own. For instance, the cross-stitch company Charles Craft sells a fabric reproduction of the Mona Lisa in a gold frame, which cross-stitchers are then invited to sew as their own masterpiece. The advertisement suggests that the consumer can not only "own" this priceless masterpiece, he or she can also create it by hand and, what's more, wear the famous Mona Lisa smile as well. It is also possible to "wear" the Mona Lisa in the form of jewelry and clothing, in necklace pendants, pins, and ties imprinted with its image, sold in novelty stores, museum shops, and on the Web. To whom then does the image belong, and who is its artist? The question of artistic ownership becomes increasingly complex in digital media, which make accessible to the average consumer many of the processes of reproduction.

Another way that famous works of art change meaning through reproduction is through both art references and the constant reworking and remaking of popular culture. We will discuss many aspects of this recycling in Chapter 7. Here, we would like to emphasize how this operates in the context of remaking famous, original images. The Mona Lisa was "remade" by several modern artists. For instance, in 1919 Marcel Duchamp drew a moustache and goatee on the famous portrait in a kind of satirical irreverence that was characteristic of Dada art, naming it L.H.O.O.Q., which when spoken in French means "she has a hot ass", and later Surrealist painter Salvador Dali redid the Mona Lisa with his own famous swirling moustache, referring back to Duchamp.

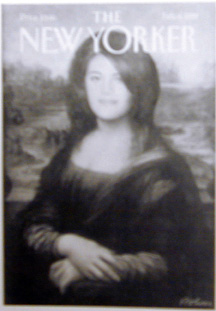

Hence, the Mona Lisa carries a range of culture references. In the cover on the next page from The New Yorker, a popular magazine about culture and politics, the Mona Lisa is evoked in an image of Monica Lewinsky, who became briefly famous in the late 1 990s for allegedly having an affair with US President Bill Clinton. There are many interesting visual puns and plays on meaning that give this image its wry humor. Both figures share dark hair and round faces, the initials ML, and names beginning with M-o-n. Both are female icons who command instant face recognition in contemporary Western culture. The model for da Vinci's Mona Lisa has remained anonymous despite endless speculation about her identity. Her appeal is attributed in part to her mystery, represented in her ambiguous smile, sometimes referred to as the most famous smile in the world. Like the Mona Lisa's model, Monica Lewinsky was (before the White House scandal) an anonymous and relatively unremarkable woman. She then became, at least briefly, as famous as the Mona Lisa, though certainly without the enigma of the woman of the original painting, whose mystery is based in part on the fact that she, unlike Lewinsky, does not.speak. Ironically, Lewinsky's image, like the Mona Lis Hence, the Mona Lisa carries a range of culture references. In the cover on the next page from The New Yorker, a popular magazine about culture and politics, the Mona Lisa is evoked in an image of Monica Lewinsky, who became briefly famous in the late 1 990s for allegedly having an affair with US President Bill Clinton. There are many interesting visual puns and plays on meaning that give this image its wry humor. Both figures share dark hair and round faces, the initials ML, and names beginning with M-o-n. Both are female icons who command instant face recognition in contemporary Western culture. The model for da Vinci's Mona Lisa has remained anonymous despite endless speculation about her identity. Her appeal is attributed in part to her mystery, represented in her ambiguous smile, sometimes referred to as the most famous smile in the world. Like the Mona Lisa's model, Monica Lewinsky was (before the White House scandal) an anonymous and relatively unremarkable woman. She then became, at least briefly, as famous as the Mona Lisa, though certainly without the enigma of the woman of the original painting, whose mystery is based in part on the fact that she, unlike Lewinsky, does not.speak. Ironically, Lewinsky's image, like the Mona Lis a in relationship to the Renaissance, may be more visually symbolic of this era in history (and its intense media focus on the private lives of public figures) than the image of the powerful man through whom she achieved fame. The remaking of this famous original thus allows this image to convey a broad set of meanings in a compact form. a in relationship to the Renaissance, may be more visually symbolic of this era in history (and its intense media focus on the private lives of public figures) than the image of the powerful man through whom she achieved fame. The remaking of this famous original thus allows this image to convey a broad set of meanings in a compact form.

Reproduced images as politics

Walter Benjamin wrote that the result of mechanical reproduction was a profound change in the function of art. He stated, "instead of being based on ritual, [art] begins to be based on another practice—politics."8 What did he mean by this? Benjamin wrote this essay in Germany in the 1 930s, as the rise of Fascism and the Nazi Party was orchestrated in part by an elaborate propaganda machine of images. Germany's Third Reich anticipated much of the contemporary use of images in politics to groom the image of political leaders and the cult value that images can produce. Its images of grandeur, monumentality, and massive regimentation are now icons for both a Fascist aesthetic and the practice of propaganda.

We often think of propaganda as a practice used exclusively by totalitarian and authoritarian governments, an obvious campaign to "sway the masses," and we will discuss this concept of propaganda at length in Chapter 5. But, the term "propaganda" can refer to any attempt to use words and images to promote particular ideas and persuade people to believe certain concepts This definition could also fit advertising images and any image with an intention to convey a political message or persuade. It is, in fact, what we mean by the use of images as politics.

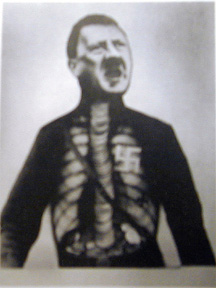

Mechanically or electronically reproduced images can be in many places simultaneously and can be combined or put with text. These capabilities have greatly increased the ability of images to captivate and persuade. In the 1 930s, German artist John Heartfield produced photo collages against the Nazis that had a biting political edge. The powerful effect of Heartfield's images is derived in part from his use of "found" photographic images to make political statements. In this image, he portrays Hitler swallowing gold coins and taking the money of the German people. The photo-collage form allows Heartfield to make a staternent. We do not read his image as realistic, but rather as a metaphor for political themes. Heartfield borrowed from the style of propaganda images at the time to make his political art, using the images of the Nazis against them. and persuade. In the 1 930s, German artist John Heartfield produced photo collages against the Nazis that had a biting political edge. The powerful effect of Heartfield's images is derived in part from his use of "found" photographic images to make political statements. In this image, he portrays Hitler swallowing gold coins and taking the money of the German people. The photo-collage form allows Heartfield to make a staternent. We do not read his image as realistic, but rather as a metaphor for political themes. Heartfield borrowed from the style of propaganda images at the time to make his political art, using the images of the Nazis against them.

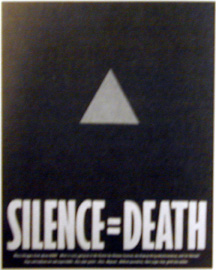

The tradition of political and protest art, which expanded in significant ways in the era of mechanical reproduction, often stands in opposition to the concept that images should be unique, sacred, and have monetary value. For instance, AIDS activists have produced images for the purpose of distributing as many symbols and messages as possible on the street, in posters, buttons, stickers, and T-shirts. These images were disseminated in the 1 980s and 1 990s in cities like New York as a means of using the street as a forum for protest art. The Silence = Death image (which has an inverted pink triangle in its center) has been distributed in many forms and even spray-painted onto sidewalks in certain cities. The value of this image comes not from its reference to any original, but from its ubiquity. It is intended to make people recognize and reconsider their passivity precisely because it is an omnipresent symbol. The triangle refers to the pink triangle that homosexuals were forced to wear in Nazi  Germany, just as Jews were forced to wear yellow stars. As such it is intended to refer to the tragic consequences of ignoring a crisis at hand. With the triangle placed upside down, this image appropriates a homophobic symbol of the past in order to create new meanings. This act of appropriation and trans-coding, or changing the meaning of the original symbol, has important political meaning precisely because it empties the original symbol, here the pink triangle, of its power. The effectiveness of the Silence = Death image to convey a message is directly related to its capacity to be multiply reproduced and to exist in many different places at the same time. The more it proliferates, the more powerful its message. Importantly, it is not a copyrighted image, but an image made to be copied and passed around—an image that is free of charge and not owned by anyone. Germany, just as Jews were forced to wear yellow stars. As such it is intended to refer to the tragic consequences of ignoring a crisis at hand. With the triangle placed upside down, this image appropriates a homophobic symbol of the past in order to create new meanings. This act of appropriation and trans-coding, or changing the meaning of the original symbol, has important political meaning precisely because it empties the original symbol, here the pink triangle, of its power. The effectiveness of the Silence = Death image to convey a message is directly related to its capacity to be multiply reproduced and to exist in many different places at the same time. The more it proliferates, the more powerful its message. Importantly, it is not a copyrighted image, but an image made to be copied and passed around—an image that is free of charge and not owned by anyone.

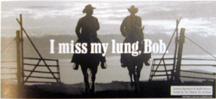

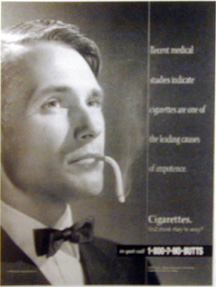

The proliferation of images through reproduction also means that they can be accompanied by different kinds of text, which can dramatically change the signification of the image. Text can ask us to look at an image differently. Words s' can direct our eyes to particular aspects of the image, indeed they can tell us what to see in a picture. This is often the case in advertising, where the text directs the viewer to read an image in a particular way. We can see that the text that accompanies the Heartfield photo collage, "He swallows gold and spits out tin-plate," explains the image to us, and makes clear its political meaning. It strongly condemns Hitler as a leader who is robbing the German people and selling them a fake message. The words "Silence = Death" give a particular meaning to the transformed pink triangle, encoding it with a complex set of meanings. Often text is combined with images as a means to jolt the viewer into reading the image differently. This effect has been widely used for public service ads, which act as adve rtisements for public policies. A widespread antismoking advertisement campaign in the USA has, among other tactics, appropriated some of the most iconic images of tobacco ads. In this image, the familiar photograph of the cowboy that signifies both cigarette smoking and masculinity, an association that Marlboro has produced through years of advertising, is given new meaning through its text. Indeed, the text here functions to produce a new sign with the image (cigarette-smoking cowboy = lung disease) specifically because of its previously established sign (cigarette smoking cowboy = masculinity). In this ad, like the remake of the Marlboro Man that we discussed in Chapter 1, the equation of cigarette smoking with sexuality and virility is reversed to connote impotence. The words serve to give these image rtisements for public policies. A widespread antismoking advertisement campaign in the USA has, among other tactics, appropriated some of the most iconic images of tobacco ads. In this image, the familiar photograph of the cowboy that signifies both cigarette smoking and masculinity, an association that Marlboro has produced through years of advertising, is given new meaning through its text. Indeed, the text here functions to produce a new sign with the image (cigarette-smoking cowboy = lung disease) specifically because of its previously established sign (cigarette smoking cowboy = masculinity). In this ad, like the remake of the Marlboro Man that we discussed in Chapter 1, the equation of cigarette smoking with sexuality and virility is reversed to connote impotence. The words serve to give these image s the opposite meaning. This appropriation depends, however, on the viewer being familiar with the original meaning. s the opposite meaning. This appropriation depends, however, on the viewer being familiar with the original meaning.

Visual technologies and phenomenology

The photographic image was primary in the rise of mechanical reproduction and the changing role of images in modernity. Subsequently, the role of images has been transformed again with the invention of cinema in the 1 890s, the development of the electronic image of television in the 1 940s and 1 950s, and, more recently, with the World Wide Web and digital imaging. Each medium has built upon and recoded the media that existed prior to it. One way of considering the difference between these media is to examine the phenomenological aspects of each.

In the most general sense, phenomenology is the belief that all knowledge and truth derives from subjective human experience and not solely from things themselves. Philosopher Edmund Husserl, who is considered the founder of the philosophy of phenomenology, rebelled against the rational age of scientific inquiry by insisting that experience cannot be known in an objective sense. He proposed, in his writings of the 191 0s and 1 920s, a science of experience of the ways we react bodily and emotionally as well as intellectually to the world around us. Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who wrote his most influential works in the 1 950s and 1 960s, emphasized the importance of recognizing bodies as the entity through which we experience the worid and emerge as individua~ subjects. He challenged the idea of mind-body dualism, that the mind and body are separate, which was central to Greek philosophy and expanded by Descartes, and he asserted instead that perception is the most important sensory register through which we can know of our embodied experiences. This in turn has particular importance for the study of practices of looking as embodied and perceptual in nature. A phenomenological understanding of images would, for instance, work against the erasure of the painter's body that takes place in the science of perspective.

The phenomenological approach has traditionally gotten short shrift in theories of film and media, where the theories of Marxism, structuralism, and psychoanalysis have clashed with certain tenets of phenomenology. Marxism places its emphasis on the collective body and material relations, not individual experience. Structural linguistics, with its focus on language and meaning, has not accounted for the physicality of voice and motor aspects of language. Psychoanalysis has not fully accounted for physiological and biological aspects of behavior, hence its understanding of the body is limited.

Perception, memory, and imagination are key concerns of phenomenological approaches to cultural analysis.9 In using phenomenology to examine visual media, we focus on the specific capacities of each medium that distinguish its properties, and the effect of these properties on our experience of the images produced in each. For instance, the phenomenology of photography consists of those properties that affect the viewer's experience of it—it is usually a paper object that we can hold in our hand or see in a book, it is created with a camera and light, and it is static as opposed to time-based. We might want to ask, then, how looking at a photograph is phenomenologically different from, say, looking at a film. The traditional context of experiencing film involves looking at a projected image on a large screen, sitting in a dark room, and having no control over the timing of the work. A film is not, like a photograph, an object we can hold in our hands. Hence, phenomenology offers a means to examine the distinct materialities of these media in terms of how each affects the viewer's experience of it, and its impact on the lived body of the viewer. Given the necessity of grounding this material difference in specific historical and political contexts, phenomenology is most useful when used in conjunction with socio-historical and cultural analyses.

Just as the invention of photography in the early 1800s signaled a broad set of social needs and desires at the time, which were related to the rise of modernism, the invention of cinema corresponded with an increased desire to visualize movement. Indeed, the invention of cinema was preceded by an interest in paintings and photographs that could visualize movement. Most notable among photographers was Eadweard Muybridge, who in the late nineteenth century produced a study of animal and human locomotion. Muybridge used an elaborate system of cameras and trip wires to take a series of images that depict the complexity of human and animal form when in motion. We will discuss his images further in Chapter 8. Photographic images of movement set the stage for the development of cinema, which necessitated both the invention of a moving picture camera and projector and a flexible form of film (celluloid) that would not break when wound on reels. Hence, the primary phenomenological differences between photography and cinema are temporality, sound, and movement. These differences allowed cinema to become a primary means of storytelling. The development of cinematic conventions of framing, camera movement, and editing has tended to facilitate the construction of narratives. Cinematic meaning is derived through the combination of images rather than from a single frame. The juxtaposition of two images to create a third meaning is a central concept of film. While in conventional films, the combination of two shots is often intended to have a seamless effectthat is unnoticed bythe viewer, there is also a tradition in experimental cinema of juxtaposing images to create meaning through contrast. In Ashputtle (1982), artist John Baldessari references this aspect of cinema. Juxtaposing a series of found still images, many presumably from films, Baldessari creates an enigmatic set of meanings. Each individual image is a glimpse of a larger unexplained narrative, and the combination of these disparate frames creates a new set of stories. In addition, each image indicates a possible set of stories about what is happening outside of its frame, referring to that which is "off screen." In this sense, the image collage creates a multi-layered space and many potential narratives. broad set of social needs and desires at the time, which were related to the rise of modernism, the invention of cinema corresponded with an increased desire to visualize movement. Indeed, the invention of cinema was preceded by an interest in paintings and photographs that could visualize movement. Most notable among photographers was Eadweard Muybridge, who in the late nineteenth century produced a study of animal and human locomotion. Muybridge used an elaborate system of cameras and trip wires to take a series of images that depict the complexity of human and animal form when in motion. We will discuss his images further in Chapter 8. Photographic images of movement set the stage for the development of cinema, which necessitated both the invention of a moving picture camera and projector and a flexible form of film (celluloid) that would not break when wound on reels. Hence, the primary phenomenological differences between photography and cinema are temporality, sound, and movement. These differences allowed cinema to become a primary means of storytelling. The development of cinematic conventions of framing, camera movement, and editing has tended to facilitate the construction of narratives. Cinematic meaning is derived through the combination of images rather than from a single frame. The juxtaposition of two images to create a third meaning is a central concept of film. While in conventional films, the combination of two shots is often intended to have a seamless effectthat is unnoticed bythe viewer, there is also a tradition in experimental cinema of juxtaposing images to create meaning through contrast. In Ashputtle (1982), artist John Baldessari references this aspect of cinema. Juxtaposing a series of found still images, many presumably from films, Baldessari creates an enigmatic set of meanings. Each individual image is a glimpse of a larger unexplained narrative, and the combination of these disparate frames creates a new set of stories. In addition, each image indicates a possible set of stories about what is happening outside of its frame, referring to that which is "off screen." In this sense, the image collage creates a multi-layered space and many potential narratives.

While the media of photography and film share many properties, in particular the mechanical process of photography (which necessitates, among other things, the development of film), the television image is phenomenologically quite different from each. It is true that for many viewers, distinctions between the television image and the film image are increasingly difficult to make, as we watch films on VCRs and television images are incorporated into film. As both become digital, these differences will lessen. Yet, by nature of the fact that it is composed electronically, the television image has a set of properties distinct from film. In the television image, the audio and video are derived from the same electronic signal. They do not require chemical developing, hence they can be seen instantly. Television images are transmitted to many different television sets at the same time. They can be.seen live, and in today's world of satellite technology, can be broadcast live around the world. They gain their value not through their aesthetic range, as is the case for many photographs and films, but through their immediacy, speed, and transmission.

The criteria that assigns more value to an original image and less to a copy, as outlined by Walter Benjamin, makes no sense when applied to television transmission. Indeed, the concept of image transmission forces us to think in different ways about the reproduction of an image, since the television image is in fact many simultaneous images in different places. However, Benjamin's argument that images that are reproduced can acquire political meaning does make sense in relation to television. As a mass medium, television is a powerful tool in the dissemination of ideas and ideologies. What gives value to a television image? In the case of news images, we could say it is its immediacy and the depiction of important events; in the case of popular culture, it is its entertainment value and widespread transmission to many TV sets at once. When we watch television we may think of ourselves as watching with a broader audience. This imagined audience may be global or national, as in the case of viewing important news events, or a group of fans, as in the case of watching TV dramas and sitcoms. We can thus say that the phenomenological properties of television affect the kinds of experiences that audiences derive from television programs.

Similarly, we can say that our experience of cQmputer images in the context of the Internet and the World Wide Web presents us with yet another phenomenological difference. When it emerged in the early 1 990s, the World Wide Web allowed for a broad range of images and graphics to become available to computer users through the Internet. We will discuss the history of the internet at more length in Chapter 9, but here we would like to note the important visual aspects of the Web. The World Wide Web became popular very quickly because of its emphasis on visual images, at a time when the idea of a graphical user interface took hold in computers. This means that computer users are now accustomed to navigating software and information on data bases through graphics and images (using a computer mouse) rather than simply through entering commands as text. Phenomenologically, however, it is important to note that the computer user's relationship to images on .the computer screen is interactive. Users make choices, browse, and move to new screens and images through hypertext links. Because the images that we access this way are digital, they can be easily downloaded onto our computers, and used in different contexts. The age of the computer, electronic imaging, and the digital thus presents a profound shift in the status of the image.

The digital image

In the 1 980s and 1 990s, the development of digital images began to radically transform the meaning of images in Western culture. Digital images differ from photographic images in that they are computer generated (or, at least, computer enhanced). Analog images bear a physical correspondence with their material referents. Analog computers used physical quantities (such as length) to represent numbers. Whereas analog images, such as photographs and most video images, are defined by properties that express value along a continuous scale, such as gradations of tone (or changes in intensity through increasing or decreasing voltage in video), digital images are encoded as information. Digital computers make calculations with data represented by digits. The pixel, the smallest unit of the visual field that makes up the digital image, is one such digit. John Berger, in his classic essay "Understanding a Photograph," claims that photographs are simply "records of things seen" and are "no closer to works of art than cardiograms."'° He is referring to the analog process of correspondence between a referent and its representation. As a set of encoded bits, a digital image can be easily stored, manipulated, and reproduced. Here we can see again how the concept of reproduction changes with electronic images. In digital images, the idea of the difference between a copy and an original is nonexistent. Indeed, a "copy" of a digital image is exactly like the "original." The value of a digital image is derived in part by its role as information, and its capacity to be easily accessed, manipulated, stored in a computer or on a web site, downloaded, etc. The idea of an image being unique makes no sense with digital images.

We can see, in retrospect, how each of the different time eras of image technology outlined earlier in this chapter (ancient art, the age of perspective, the modern era of mechanical reproduction, and the postmodern era of electronic and computer imaging) entails a different set of criteria by which images are valued and perceived. The premechanical image, such as the painting that was situated within a specific place, gained its cultural value from being unique. It had a role in ritual and a cult value precisely because it was one of a kind. The mechanically reproduced image gains its value through its reproducibility, potential distribution, and role in the mass media. It can disseminate ideas, persuade viewers, and circulate political ideas. The digital and virtual image gains its value from its accessibility, malleability, and information status. All of these images with their different meanings coexist in our societies today.

The increased versatility of digital images raises important questions about the cultural concept of photographic truth. As we noted in Chapter 1, it has always been possible to "fake" realism in photographs. Digital techniques have made it possible to build on this ability to artificially construct realism. For example, digital images that look like photographs can be produced without a camera. In semiotic terms, this means that the photographic image is produced without a referent, or a real-life component, in the real. As we noted in Chapter 1, semiotician Charles Peirce used a three-part system to identify signs, with the referent referring to the object itself, rather than its representation in an image or word. The meaning of a photograph is thus derived from the belief that it has a referent in the real.

Peirce's work has been important for looking at images because of the distinctions that he makes between different kinds of signs and their relationship to the real. Peirce defined three kinds of signs: iconic, indexical, and symbolic. As conventions, signs are often a kind of short-hand language for viewers of images, and we are often incited to feel that the relationship between a signifier and signified is "natural." For instance, we are so accustomed to identifying the American flag with the United States, a rose with the concept of romantic love, and a dove with peace that It is difficult to recognize that their relationship is constructed rather than natural.

- Peirce's definition of iconic is different from the general meaning of icons that we discussed in Chapter 1. Iconic signs resemble their object in some way. Hence forms of visual representation such as paintings and graphs are iconic, as are photographs and film and television images.

- Symbolic signs, unlike icons which resemble their objects, bear no obvious relationship to their objects. Symbols are created through an arbitrary (one could say "unnatural") alliance of a particular object and a particular meaning. For example, languages are symbolic systems which use conventions to establish meaning. There is no natural link between the word "cat" and an actual cat; the convention in the English language gives the word its signification. Symbolic signs are inevitably more restricted in their capacity to convey meaning in that they refer to learned systems. Someone who does not speak English can probably recognize an image of a cat (an iconic sign), whereas the word "cat" (a symbolic sign) will have no meaning to them.

- Indexical signs as defined by Peirce involve an "existential" relationship between the signifier and the signified. This means that they have coexisted in the same place at some time. Peirce uses as examples the symptom of a disease, a pointing hand, and a weathervane. Fingerprints are indexical signs of a person, and photographs are also indexical signs that testify to the moment that the camera was in the presence of its subject. Indeed, while photographs are both iconic and indexical, their cultural meaning is derived in large part from their indexical meaning as a trace of the real.

Importantly, though, most digital images and simulations are not indexical, since they cannot be said to have been in the presence of the real world that they depict. For instance, an image that inserts people digitally into a landscape where they have never been does not refer to an actual moment in time. This raises the question, what happens to the idea of photographic truth when an image that looks like a photograph is created on a computer with no camera at all; In Peirce's terms, this marks a fundamental shift in meaning from the photograph to the digital image. Here, index gives way to icon, since we take these computer-generated images to resemble real-life subjects.

Of course most of the images that we see on a daily basis have been modified in some way. Most advertising images are produced with a significant amount of airbrushing and modification. This means that the so-called "natural" images of fashion models have all been highly doctored and manipulated, with wrinkles and blemishes erased, lips enhanced, features moved, and colors changed. The advertising images that entice consumers to try to look like certain models thus offer up an ideal that, in fact, has no basis in reality. This construction of the idea of a perfect face or body is intended of course to produce feelings of inadequacy in viewers, so that they will feel impelled to purchase more consumer products. Hence, as we will discuss further in Chapter 6, the photographic "truth" in advertising has always been highly questionable.

A different set of questions is raised when we consider the impact of digital imaging on news and historical images. It is now a common practice to have personal photographs digitally reconfigured, to take now out-of-favor relatives out of wedding pictures, for instance, or to erase ex-boyfriends from treasured images. In most cases, this kind of toying with the historical record is relatively harmless. Yet, we can also imagine a context in which all historical images are up for grabs. There has been a long tradition in certain countries of rearranging photographs to retell history, such as the tradition of erasing deposed politicians from official historical images in the former Soviet Union; these technical procedures are now vastly improved and widely accessible with digital technology. A different set of questions is raised when we consider the impact of digital imaging on news and historical images. It is now a common practice to have personal photographs digitally reconfigured, to take now out-of-favor relatives out of wedding pictures, for instance, or to erase ex-boyfriends from treasured images. In most cases, this kind of toying with the historical record is relatively harmless. Yet, we can also imagine a context in which all historical images are up for grabs. There has been a long tradition in certain countries of rearranging photographs to retell history, such as the tradition of erasing deposed politicians from official historical images in the former Soviet Union; these technical procedures are now vastly improved and widely accessible with digital technology.